Article continues below

In late 18th-Century Europe, a new fashion led to an international scandal. In fact, an entire social class was accused of appearing in public naked.

The culprit was Dhaka muslin, a precious fabric imported from the city of the same name in what is now Bangladesh, then in Bengal. It was not like the muslin of today. Made via an elaborate, 16-step process with a rare cotton that only grew along the banks of the holy Meghna river, the cloth was considered one of the great treasures of the age. It had a truly global patronage, stretching back thousands of years – deemed worthy of clothing statues of goddesses in ancient Greece, countless emperors from distant lands, and generations of local Mughal royalty.

There were many different types, but the finest were honoured with evocative names conjured up by imperial poets, such as "baft-hawa", literally "woven air". These high-end muslins were said to be as light and soft as the wind. According to one traveller, they were so fluid you could pull a bolt – a length of 300ft, or 91m – through the centre of a ring. Another wrote that you could fit a piece of 60ft, or 18m, into a pocket snuff box.

Dhaka muslin was also more than a little transparent.

While traditionally, these premium fabrics were used to make saris and jamas – tunic-like garments worn by men – in the UK they transformed the style of the aristocracy, extinguishing the highly structured dresses of the Georgian era. Five-foot horizontal waistlines that could barely fit through doorways were out, and delicate, straight-up-and-down "chemise gowns" were in. Not only were these endowed with a racy gauzy quality, they were in the style of what was previously considered underwear.

In one popular satirical print by Isaac Cruikshank, a clique of women appear together in long, brightly coloured muslin dresses, though which you can clearly see their bottoms, nipples and pubic hair. Underneath reads the description, "Parisian Ladies in their Winter Dress for 1800".

Meanwhile in an equally misogynistic comedic excerpt from an English women's monthly magazine, a tailor helps a female client to achieve the latest fashion. "Madame, ’tis done in a moment," he assures her, then instructs her to remove her petticoat, then her pockets, then her corset and finally her sleeves… "‘Tis an easy matter, you see," he explains. "To be dressed in the fashion, you have only to undress."

Still, Dhaka muslin was a hit – with those who could afford it. It was the most expensive fabric of the era, with a retinue of dedicated fans that included the French queen Marie Antoinette, the French empress Joséphine Bonaparte and Jane Austen. But as quickly as this wonder-cloth struck Enlightenment Europe, it vanished.

Story continues below

19th century satirical printmakers enjoyed highlighting the perils of muslin dresses, such as the risk of appearing nude in strong sunlight, wind or rain (Credit: Alamy)

By the early 20th Century, Dhaka muslin had disappeared from every corner of the globe, with the only surviving examples stashed safely in valuable private collections and museums. The convoluted technique for making it was forgotten, and the only type of cotton that could be used, Gossypium arboreum var. neglecta – locally known as Phuti karpas – abruptly went extinct. How did this happen? And could it be reversed?

A fickle fibre

Dhaka muslin began with plants grown along the banks of the Meghna river, one of three which form the immense Ganges Delta – the largest in the world. Every spring, their maple-like leaves pushed up through the grey, silty soil, and made their journey towards straggly adulthood. Once fully grown, they produced a single daffodil-yellow flower twice a year, which gave way to a snowy floret of cotton fibres.

These were no ordinary fibres. Unlike the long, slender strands produced by its Central American cousin Gossypium hirsutum, which makes up 90% of the world’s cotton today, Phuti karpas produced threads that are stumpy and easily frayed. This might sound like a flaw, but it depends what you’re planning to do with them.

Indeed, the short fibres of the vanished shrub were useless for making cheap cotton cloth using industrial machinery. They were fickle to work with, and they’d snap easily if you tried to twist them into yarn this way. Instead, the local people tamed the rogue threads with a series of ingenious techniques developed over millennia.

You might also like:

- The unexpected way Bollywood could help millions

- Bangladesh: The country disappearing under rising tides

- The Indian megacity digging a million wells

The full process involved 16 steps, each of which was so specialist, it was carried out by a different village around Dhaka, which was then part of Bengal – some in what is now Bangladesh, some in what is now the Indian state of West Bengal. It was a true community effort, involving the young and old, men and women.

First, the balls of cotton were cleaned with the tiny, spine-like teeth on the jawbone of the boal catfish, a cannibalistic native of lakes and rivers in the region. Next came the spinning. The short cotton fibres required high levels of humidity to stretch them, so this stage was performed on boats, by skilled groups of young women in the early morning and late afternoon – the most humid times of day. Older people generally couldn’t spin the yarn, because they simply couldn’t see the threads.

Dhaka muslin was a favourite of Joséphine Bonaparte, the first wife of Napoleon, who owned several dresses inspired by the classical era (Credit: Alamy)

"You'd get tiny, tiny little joins between the cotton fibres, where they were linked together," says Sonia Ashmore, a design historian who authored a book about muslin in 2012. "It lent the surface a kind of roughness, which gives a very nice feel."

Finally, there was the weaving. This part could take months to complete, as classic jamdani designs – mostly geometric shapes depicting flowers – were integrated directly into the cloth, using the same technique that was used to create the famous royal tapestries from medieval Europe. The result was a minutely detailed artwork rendered in thousands of silvery, silky strands.

An Asian wonder

The region’s Western customers found it hard to believe that Dhaka muslin could possibly have been made by human hands – there were rumours that it was woven by mermaids, fairies and even ghosts. Some said that it was done underwater. "The lightness of it, the softness of it – it was like nothing we have today," says Ruby Ghaznavi, vice president of the Bangladesh National Craft Council.

The same weaving process continues in the region to this day, using lower-quality muslin from ordinary cotton threads instead of Phuti karpas. In 2013, the traditional art of jamdani weaving was protected by Unesco as a form of intangible cultural heritage.

But the real feat was the thread counts that could be achieved.

It was all going so well – then the British turned up

Higher thread counts are seen as desirable because they make materials softer, and tend to wear better over time – the more strands there are to begin with, the more there will remain to hold the fabric together when some begin to fray.

Saiful Islam, who runs a photo agency and leads a project to resurrect the fabric, says most versions made today have thread counts between 40 and 80 – meaning they contain roughly that number of criss-crossing horizontal and vertical threads per square inch of fabric. Dhaka muslin, on the other hand, had thread counts in the range of 800-1200 – an order of magnitude above any other cotton fabric that exists today.

Though Dhaka muslin vanished more than a century ago, there are still intact saris, tunics, scarves and dresses in museums today. Occasionally one will resurface at a high-end auction house such as Christie’s and Bonhams, and sell for thousands of pounds.

A colonial shambles

"The trade was built up and destroyed by the British East India Company," says Ashmore.

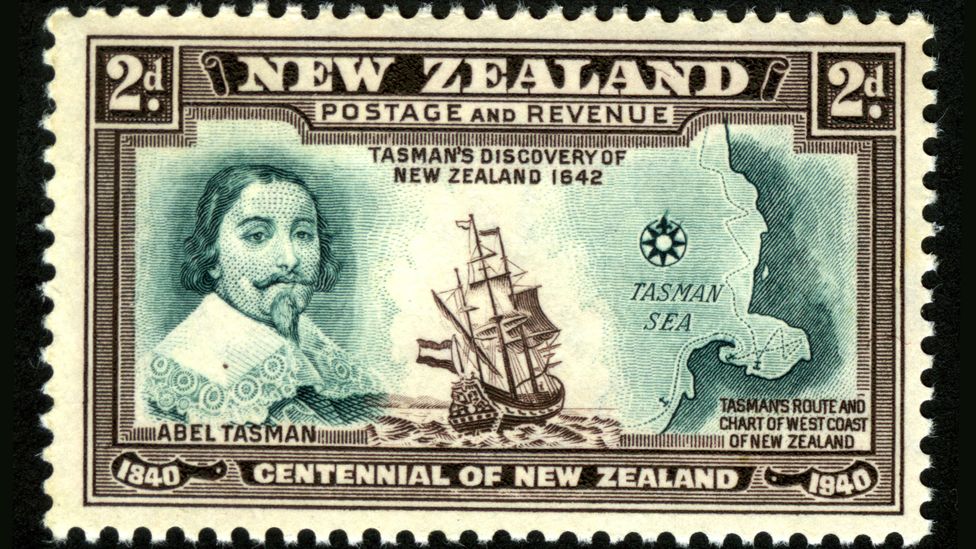

Long before Dhaka muslin was draped over aristocratic women in Europe, it was sold across the globe. It was popular with the Ancient Greeks and Romans, and muslin from "India" is mentioned in the book The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, authored by an anonymous Egyptian merchant around 2,000 years ago.

Dhaka muslin came in thread counts up to 1,200, but the highest achieved in recent years is 300 (Credit: Drik/ Bengal Muslin)

The Roman author Petronius may have been the first person on record to raise an eyebrow over its transparency, writing: "Thy bride might as well clothe herself with a garment of the wind as stand forth publicly naked under her clouds of muslin." Over the coming centuries, the fabric is praised in the works of the renowned 14th-Century Berber-Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta and the prolific 15th-Century Chinese voyager Ma Huan, as well as many others.

But the Mughal era was arguably the fabric’s heyday. The South Asian empire was founded in 1526 by a warrior chieftain from what is now Uzbekistan, and by the 18th Century it ruled across the entire Indian subcontinent. During this period, muslin was traded extensively with merchants from Persia (modern-day Iran), Iraq, Turkey and the Middle East.

The cloth was thoroughly endorsed by Mughal emperors and their wives, who were rarely painted wearing anything else. They went so far as to bring the best weavers under their patronage, employing them directly and banning them from selling the very finest cloth to others. According to popular legend, its transparency led to yet more trouble when the emperor Aurangzeb scolded his daughter for appearing in public naked, when she was, in fact, ensconced in seven layers of it.

It was all going so well – then the British turned up. By 1793, the British East India Company had conquered the Mughal empire, and less than a century later the region was under the control of the British Raj.

Dhaka muslin was first showcased in the UK at The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in 1851. This spectacular event was the brainchild of Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert, intended to showcase the wonders of the British Empire to their subjects. Some 100,000 objects from the farthest corners of the globe were gathered together in a glittering glass hall, Crystal Palace, which was 1,851ft (564m) long and 128ft (39m) high.

At the time, a yard of Dhaka muslin fetched prices ranging from £50-400, according to Islam – equivalent to roughly £7,000-56,000 today. Even the best silk was up to 26 times less expensive.

Spinning phuti karpas cotton is notoriously tricky – if you get it wrong, the thread will snap (Credit: Drik/ Bengal Muslin)

But while Victorian Londoners were fawning over the fabric, those who produced it were being pushed into debt and financial ruin. As the book Goods from the East, 1600–1800 explains, the East India Company first started meddling with the delicate process of manufacturing Dhaka muslin in the late 18th Century.

First the company replaced the region’s usual customers with those from the British Empire. "They really put a stranglehold on its production and came to control the whole trade," says Ashmore. Then they came down hard on the industry, pressurising the weavers to produce higher volumes of the fabric at lower prices.

"You needed such a special skill to convert it [Phuti karpas] into cloth," says Islam. "It's a very arduous, expensive process – and at the end of the day, after all that you'd only get about eight grammes of fine muslin for one kilogramme of cotton."

As weavers struggled to keep up with these demands, they fell into debt, explains Ashmore. They were paid upfront for the cloth, which could take up to a year to make. But if the fabric was not considered to be up to the required standard, they would have to pay it all back. "They could never really keep up with these debt repayments," she says.

The final blow came from competition. Colonial enterprises such as the East India Company had been engaged in documenting the industries they relied on for years, and muslin was no exception. Every step of the process of making the fabric was recorded in meticulous detail.

As the European thirst for luxury fabrics increased, there was an incentive to make cheaper versions closer to home. In the county of Lancashire in northwest England, the textile baron Samuel Oldknow combined the British Empire’s insider knowledge with state-of-the-art technology, the spinning wheel, to supply Londoners with vast quantities. By 1784, he had 1,000 weavers working for him.

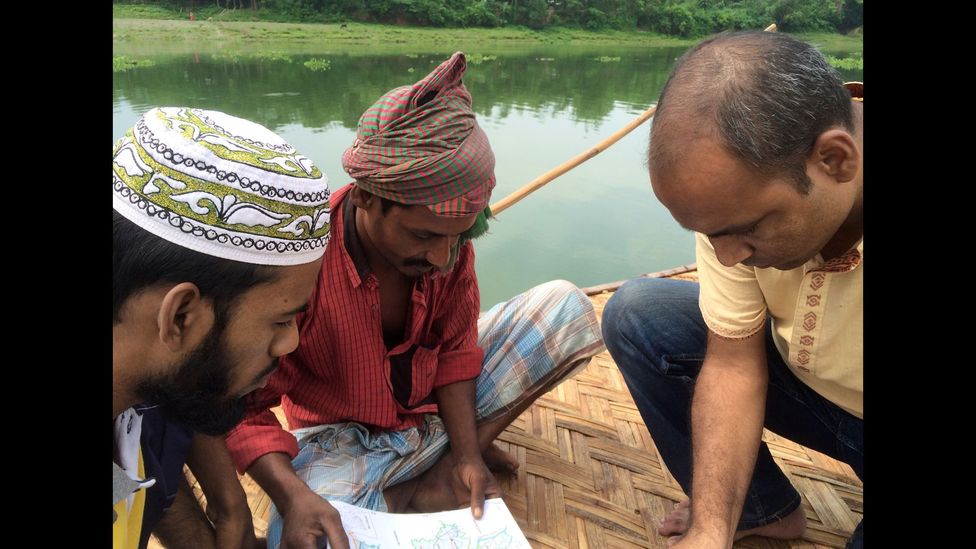

The team at Bengal Muslin enlisted the help of local villagers during the search for the lost plant (Credit: Drik/ Bengal Muslin)

Though the British-made muslin didn’t come close to Dhaka’s original – it was made with ordinary cotton, and woven at significantly lower thread counts – the combination of decades of mistreatment and a sudden decline in the need for imported textiles killed it off for good.

As war, poverty, and earthquakes struck the region, some weavers switched to making lower-quality fabrics, while others became full-time farmers instead. In the end, the whole enterprise collapsed.

"I think it’s important to remember that it was really a family occupation – we often talk about the weavers and how fantastic they were, but behind their work was the women, doing the spinning," says Hameeda Hossain, a human rights activist who has written a book about the muslin industry in Bengal. "So the industry involved a lot of people."

As the generations passed, the knowledge of how to make Dhaka muslin was forgotten. And with no one to spin its silky threads, the phuti karpas plant, which had always been hard to tame – no one had been able to grow it away from the Meghna river – retreated back into wild obscurity. The legend of the loom was no more.

A second chance

Islam was born in Bangladesh and moved to London about 20 years ago. He first became aware of Dhaka muslin in 2013, when the company he works for – Drik – was approached about adapting a British exhibition on the material for a Bangladeshi audience. They felt that it was lacking in detail, so they conducted their own research.

Over the next year, Islam and colleagues met people from the local craft industry, explored the region where it had been produced, and looked for tangible examples of Dhaka muslin at museums in Europe. "The V&A has a superb collection with hundreds of pieces of it," he says. "And if you go to the English Heritage Trust they've got 2,000 pieces. And yet Bangladesh didn't have any."

The team eventually curated several exhibitions on the subject, commissioned a film and published a book, authored by Islam. At some point, they started to think that maybe, just maybe, it might be possible to bring the legendary fabric back. Together they founded Bengal Muslin, a collaborative enterprise aimed at doing just that.

Resurrected phuti karpas cotton plants look identical to the kind used to grow Dhaka muslin hundreds of years ago (Credit: Drik/ Bengal Muslin)

The first task was to find a suitable plant. Though there are no phuti karpas seeds in any collection today, they found a neat booklet of its dried, preserved leaves at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, from the 19th Century. From this, it was possible to sequence its DNA.

Armed with their target’s genetic secrets, the team went back to Bangladesh. They looked at historical maps of the Meghna river and compared them to modern satellite images to see how its course had changed over the last 200 years, and find the best spots for potential candidates. Then they hired a boat and scoured its immense breadth – it’s 12km (7 miles) wide in places – for wild plants that resembled old drawings.

Any promising options were sequenced and compared to the original. Eventually they found a 70% match – a dishevelled shrub which may have had phuti karpas ancestors.

To grow it, they initially settled on a plot of land on a small island in the middle of the Meghna, in Kapasia, 30 km (19 miles) north of Dhaka. "It was a very ideal spot. The land is fertile because it was formed through the accumulation of river sediment," says Islam. It was there that in 2015, they planted some test seeds. Soon there were orderly rows of pluti karpas among the dry earth – the first to be cultivated for more than a century.

The team harvested their first batch of cotton the same year. Though they didn’t yet have enough of the resurrected plants to make 100% authentic Dhaka muslin, they collaborated with Indian spinners to combine ordinary and phuti karpas cotton into a hybrid thread. Next it was time for the weaving – and this proved to be trickier than expected.

Because there are still weavers in Bangladesh making jamdani muslin, albeit coarser versions at lower thread counts, initially Islam hoped to simply upgrade their skills and teach them how to produce a higher-quality product that’s closer to the old fabric.

Many of the skills needed to make Dhaka muslin have been lost which makes matching the quality of the fabric a challenge (Credit: Drik/ Bengal Muslin)

"But none of them wanted to work on this, as a matter of fact," says Islam. When he told them he wanted to make 300-thread count saris, "they all said that this is crazy".

"They said: 'Thank you very much for telling us that story and heritage, but no thanks’," he says. Out of the 25 people he approached, one eventually agreed.

Most weavers in the region are poor, and work in simple huts. So Al Amin, now their master weaver, agreed to have temperature controls and humidifiers added to his workshop, to create the specific conditions needed for making this tricky fabric. Meanwhile some of the 50 or so tools required were no longer available, so the team made their own. One example is the shana, a piece of bamboo cut to have thousands of artificial teeth that can keep the thread in place while it’s worked.

Six gruelling months, many more improvisations and plenty of snapped threads later, Amin had made a 300 thread count sari – nowhere near the original Dhaka muslin standard, but significantly higher than any weaver had achieved for generations. "He had the dogged patience that was needed to work with us," says Islam. "We contributed 40% of the effort, but the rest came from him."

Fast-forward to 2021 and the team have made several saris from their hybrid muslin, which have already been exhibited all over the world. Some have been sold for thousands of pounds – and Islam feels the reception they received proves the fabric has a future. "In this day and age of mass production, it's always interesting to have something special. And the brand is still powerful," he says.

Today the team have plants growing continuously, though they were forced to abandon the old farm plot due to flooding issues. Now they’re growing the resurrected phuti karpas on a nearby riverbank, which has the added benefit of being accessible without a boat. Islam hopes that one day they’ll be able to make a pure Dhaka muslin sari at an even higher thread count.

As it happens, so does the Bangladeshi government, who have given the project their backing. "It’s a matter of national prestige," says Islam, who is also keen to upgrade the country’s image. "It’s important that our identity is not poor, with a lot of garment industries, but also the source of the finest textile that ever existed," he says.

Who knows, perhaps soon a new generation will be wearing this ancient fabric – and grappling with its somewhat risqué transparency.

* Zaria Gorvett is a senior journalist for BBC Future and tweets @ZariaGorvett

--

This article was updated on 17 March 2021. The original version stated that the rediscovered phuti karpas were grown on an island in the middle of the Ganges, in northerm India. In fact the land was on the Meghna river, in Bangladesh.

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

No comments:

Post a Comment